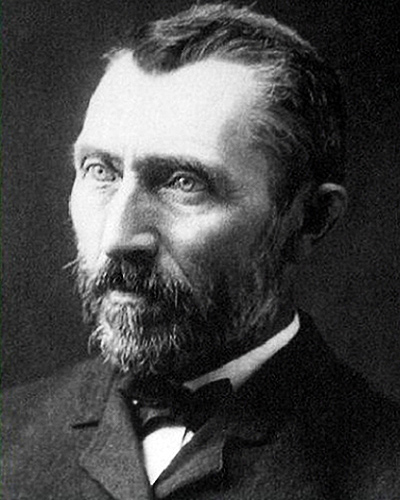

Vincent van Gogh's work as an artist has often been overshadowed by speculation about the state of his mental health. However, as the opening quote shows, he was capable of assessing his own personality lucidly and with great honesty.

"...A great fire burns within me, but no one stops to warm themselves at it, and passers-by only see a wisp of smoke..."

Vincent van Gogh

His skill as an artist enabled him to reach a reality beyond the surface of life that others could not see. At the same time, this ability distanced him from others, damaging his personal relationships and friendships through the intensity and clarity of his vision. This artistic vision, it might be argued, began in childhood, when religion and nature established themselves as the two great forces that would drive his creativity. Born the son of a Dutch minister in 1853, it was inevitable that religion would be one of the more powerful of his youthful influences. The family were well-off and genteel, and his mother in particular raised the children to have an awareness of the family’s status and respectability.

Van Gogh himself wrote of the coldness of his upbringing, and descriptions of his youth seem to indicate that he showed classic signs of introversion. He loved nature, drawing, and simply walking in the countryside, and was content in his own company. It would hardly be surprising that carrying a weight of family expectation on his shoulders would cause problems for an introspective, creative child, though his mother also encouraged his creativity through drawing. Certainly at least one of his sisters commented on the oddness of her brother’s behaviour, though against this must be set the family’s obviously strict sense of what was conventional and correct.

In theory, van Gogh's background should have been an ideal one for any young man with artistic talent, or rather artistic ambitions. His family connections included an Uncle Vincent (known as Uncle Cent) who was an art dealer for the internationally successful firm Goupil & Cie. Through Uncle Cent, the young Vincent joined the company and went to work in London.

At first, he was very successful in his work and earning a good salary. However, his time as a clerk at the company probably marks the beginning of his self-awareness that he was an outsider; the art brokering world, representing as he saw it the commodification of artists, did not appeal to him. Further disillusioned by the disappointment following his first infatuation, he returned to Paris to work in the company’s office but was soon dismissed.

Undoubtedly, van Gogh's inability to commit himself to a settled trade was of concern to his parents, a generational conflict that is not unknown to this day. Attempts to make more formal studies in art were unsuccessful. His firm Christian belief led him to spend time as a teacher and missionary, but here too, he rejected formal studies, failing the necessary examinations several times. His nature drew him to an ascetic, monastic lifestyle that brought no support from either family or the religious authorities. This austere interpretation of Christianity would initially influence both his choice of subjects and their treatment in his paintings.

The variance between what was expected of him and his own ideas and beliefs inevitably led to discord and quarrels with his family. The intensity of his attachments, whether to people, places, beliefs or ideas, would be fundamental to his creativity. However, it was so far removed from the understanding of those who loved him that it is likely the divergence contributed in some way to his own mental health issues. By 1880 his father was recommending that his son be placed in the local asylum.

His intense infatuation with his widowed cousin, Cornelia Vos-Stricker, known as “Kee” created further complications within the family. Her rejection of him was also the catalyst for van Gogh’s first identifiable psychotic episode, when he would have burned his hand severely in the flame of a lamp, but was apparently prevented from doing so by his uncle’s intervention.

Yet van Gogh was also able to draw support and encouragement from some members of his family throughout his brief life. His relationship with his beloved brother Theo was recorded in the numerous letters they exchanged which were published after the brothers’ deaths by Theo’s widow. Without Theo’s encouragement and financial support, it is unlikely that Vincent’s remarkable artistic legacy would have existed. Another relative, the successful artist Anton Mauve, could have played the part of mentor to Vincent van Gogh, and to a certain extent did so. However, Mauve appears to have decided to end all contact with van Gogh due to the latter’s relationship with Clasina Maria "Sien" Hoornik. Van Gogh’s father finally exerted sufficient pressure to force his son to leave Sien.

This polarity within his family life – meeting both tender loving care without judgement, as well as coldness, rejection and manipulation – has to be viewed as one of the key influences on his life as an artist. Art itself would exert a two-fold influence on van Gogh. On the one hand, the creative process, like the countryside and nature itself, absorbed and released him, perhaps freed him from the treadmill of an obsessive mind for as long as he was painting. On the other, his art could be a source of great conflict and pain, particularly in his relationship with the painter Gauguin.

Van Gogh's own artistic influences included the work of Millet, whose painting “The Gleaners” showed the world, through the simple dignity of peasants working in the field, that realistic imagery of ordinary people could also work as a type of metaphor, creating a timeless world in which the rhythms of nature and the seasons of man worked together in harmony. The influence of this can be clearly seen in van Gogh’s work, from the early shadowy, almost monochromatic imagery of “The Potato Eaters” to his vibrant Arles period, with its strikingly warm yellows and reds and images of sunflowers and vineyard workers.

The metaphorical aspect of van Gogh's work has been frequently noted by biographers and commentators on his letters. His use of Biblical and literary imagery in both his correspondence and his art is hardly surprising given his education, his home background and his time spent in England where he read the work of George Eliot and Dickens. His love of French writers such as Balzac, Voltaire, and particularly Zola, adds further depth to this aspect of his creativity. It is notable that all these writers wrote of “ordinary” people in extraordinary ways, from the larger than life characters of Dickens to the teeming street and theatre life of Zola.

In van Gogh's art, literary metaphors took on visual form. The working class people and agricultural labourers that he met were painted not only for their own sakes and as examples of individuals far removed from his own relatively well-to-do origins; they were also visual examples of Biblical parables. In his paintings of peasant and workers, we see the sowers of seed, the workers in the vineyard where grows the true vine, the harvesters and the fishermen.

Animals also appear in van Gogh's work to provide metaphors as well as examples of the rich diversity of a living universe. The exquisite kingfisher in his painting "Kingfisher by the Waterside” is a beautiful evocation of the natural world, and it might also represent the "fisher king" of Christian myth. The clarity and vibrancy of the little bird waiting patiently by the river catches at the heart of the observer as though they were seeing it in reality.

References to tired donkeys and worn-out horses in his art are reminders of the brief and exhausting lives of working people, remote from the privileged lives of those they serve. Probably originally impelled by his own Christian upbringing and natural sense of concern for the poor, van Gogh’s paintings of workers and peasants are not mere observations. With his own “great fire” driving him on, it was not enough for van Gogh to simply record his concern. He had to live with them, amongst them, to become, as far as was possible, one of their own.

While there might appear to be a great irony in this - after all, van Gogh was the child of a privileged background himself, and it was wealth provided by other members of his family that enabled him to paint – nonetheless his ambition was sincere. His intention to repay the generosity of his brother through sales of his paintings was also genuine, and undoubtedly his failure to do this would have been yet another cause for anxiety in the mind of a nervous, and often lonely, man. He was also sincere in his beliefs that his art was not for the wealthy, but for all humanity. He shunned sophistication and lauded feeling, with feeling for one’s fellow beings representing the purpose of both art and life itself.

Yet possibly his sense of loneliness and isolation, the source of a great deal of his illness and alcoholism, was also the key to his genius. The almost supernatural reality of the paintings of his own room in Arles, playing with the conventions of perspective, shape and form to make a “simplification [of] a grander style of things” takes the viewer into a world that is at once recognisable and yet “through the looking-glass”. Vincent wrote to Theo that: “The shading and the cast shadows are suppressed, it is painted in free flat washes like the Japanese prints…”, a reference to their shared interest in the art of Japan, which also informed his own creativity. In fact, van Gogh executed several paintings in Japanese style, as well as finding inspiration for his work such as “Almond Blossom” in the Japanese tradition.

A younger contemporary of Cézanne and Seurat, Vincent van Gogh benefited from their experiments in colour, perspective and form. The aim was not to represent reality, but to explore the potential that had begun with impressionism and then developed through Seurat’s pointillism. The work of each of these artists prefigured modern art and Vincent van Gogh’s contribution was to raise emotion above realism. How the painter felt and responded to what he saw; that was fundamental to the new art, not the technical ability to create an accurate image of the subject, whether landscape, portrait or still life.

At times van Gogh painted in a frenzy, producing a painting a day and driving himself to the verge of insanity. The sheer quantity of van Gogh’s work means that there are always new avenues to explore in his lesser-known artworks. His youthful satirical work such as “Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette” seems to anticipate both the surrealists and the post-modernists. It has all the qualities that could make it a macabre favourite as a poster in student houses, as a counterpoint to the sunflowers and cypresses of his later work that also proved so popular.

Whether living with his parents in respectable Etten in the Netherlands in his earlier life, or held within the confines of an Arles hospital or the Saint-Rémy-de-Provence asylum as he was in later life, van Gogh’s visual power never failed him. He painted through his despair, literally, describing his “moods of indescribable anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time and fatality of circumstances seemed to be torn apart for an instant”.

After his notorious confrontation with Gauguin, whom he threatened with a razor, according to Gauguin’s account, van Gogh committed the act of self-harm for which he is famous; he removed his ear with the razor and sent it to a woman in a brothel. Even this was translated into art, through his two self-portraits of 1889, entitled “Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe” and “Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear”, which is now in the Courtauld Institute, London.

Everything he saw was recreated in his own visionary style. Throughout his life, van Gogh painted his doctors, his family, the people he encountered, the natural world and the human template of agriculture and viniculture that was imposed on it. He painted animals, flowers, trees, churches and the gardens and wards of the hospitals of which he was an inmate. He painted his rooms and the hot and dusty roads that led past the shuttered houses and wheat fields with their ominous crows.

And above all, he painted a living cosmos. The sun and moon are characters in van Gogh’s paintings, powerful and personal. Their presence in his landscapes is as potent as those of tarot cards, casting their influence over the land, its people and animals. In many ways his masterpiece “The Starry Night” can be viewed as the culmination of his torment, his talent and his cosmic vision. While van Gogh acknowledged the influence of Delacroix, the painting is also likely to be a tribute to Jean-François Millet, whose own work “Starry Night” creates a night sky that is as spectacular as a fireworks show, with shooting stars that streak across leaving trails of light behind them.

In van Gogh's whirling, swirling sky, a recalled image of the view through his asylum window before dawn, the observer is reminded that stars are suns, many of them vastly larger than our own. The image has been called apocalyptic and cataclysmic. However, the sense of awe that fills the painting is also familiar and uplifting. His comment to Theo suggests that was the case for van Gogh: “Why, I say to myself, should the spots of light in the firmament be less accessible to us than the black spots on the map of France? Just as we take the train to go to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to go to a star."

Taking death to go to a star, a "great fire" that burns beyond this world, is a fitting epitaph for the artist whose own passion burned so brightly that people turned away from it while he was alive. In this world, but not of it, Vincent van Gogh never craved the fame that came to his life and his work posthumously. Towards the end of his life, he passed a comment in a letter to his brother Theo about painters being "increasingly at bay". Whether this was an unconscious reflection of his own state of mind, it is a poignant comment from an artist whose nature meant he often felt at bay in a cold world that did not recognise his creative fire.

Influences on Vincent van Gogh

Jean-Francois Millet Anton Mauve Claude Monet Honoré Daumier Eugène Delacroix Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Paul Signac Theo van Gogh Impressionism Pointillism JaponismeFamous Artists Influenced by Vincent van Gogh

Pablo Picasso Henri Matisse Paul Klee Willem de Kooning Paul Gauguin Albert Aurier Camille Pissarro Fauvism Symbolism Expressionism- English

- Deutsch

- Van Gogh Pinturas (Português)

- Van Gogh Obras (Español)

- Van Gogh Peintures (Français)

- Van Gogh Pittura (Italiano)

- Van Gogh Schilderijen (Nederlands)