Stanley Spencer was one of the most significant British artists of the inter-war period. His work is sometimes described as quintessentially English, yet his is often a distorted, even grotesque vision of rural and industrial Britain.

The Essence of Stanley Spencer

The misshapen and fantastic images he created have their own persuasive appeal, as though the artist viewed the world through a deformed yet illuminating lens and invited the observer to look through it too. His work is unflattering and completely human, devoid of pity, yet rich in compassion and redemption.

Cookham, the village which he loved and where he spent most of his life, becomes the location for extraordinary events; the dead are resurrected and mingle with angels and Biblical characters in an everyday fashion. On the battlefields of WWI, soldiers raised from the dead reach out to one another through barbed wire and barricades of fallen crosses.

His art reflects an intensely Christian faith yet is like no orthodox or even nonconformist vision. It is uniquely his own, the product of his own unconventional upbringing and path through life.

Early Life

Spencer was born in Cookham, Berkshire, in 1891. This picture-book rural community, the archetypal Thames-side village, also provided inspiration for the author of "The Wind in the Willows", Kenneth Grahame. Cookham is famous for its Swan Upping ceremony, during which, in Spencer’s day, the Thames swans were caught and marked on the beak by officials of the Crown and the Vintners' and Dyers' Companies.

It is an activity that dates back to medieval times. In his twenties, just before the outbreak of war, Spencer began to paint this seasonal incidence of the bizarre within the regular rhythms of everyday rural life. It was just one of the elements of Cookham that contributed to his artistic vision, the swans perhaps providing the later inspiration for the wings of his everyday angels resting in Cookham churchyard to watch the resurrection. War intervened, and he eventually returned to this work with difficulty after serving on the Eastern Front for over two years.

Spencer's family was an unconventional one. In fact, the word eccentric is frequently applied to the Spencers, William (also known as Par) and Anna Caroline Spencer and their numerous children. Stanley was the eighth of those that survived. Par taught music and the family was encouraged to be creative, Stanley and his brother Gilbert taking lessons with a local artist called Dorothy Bailey.

The family was comfortably off, but not rich enough to send Stanley to a private school, so he was educated at home by his sisters. Eventually, William Spencer obtained the patronage of Lord and Lady Boston to find a place for Stanley at the Maidenhead Technical Institute. In 1908 he went to the Slade School of Art in London to study among artists who would become luminaries of the twentieth century, including Paul Nash, Dora Carrington, Mark Gertler and Isaac Rosenberg.

Early Work and Connection to his Local Surroundings

His contemporaries called him "Cookham" because of his attachment to his home. He was briefly part of the Slade group known as the Neo-Primitives. However, throughout his life Spencer's work would defy categorisation or compartmentalisation as part of any major art movement.

From 1908 to 1912, Spencer painted and exhibited a number of works, in which some of his lifelong approaches and themes were already clearly defined. His painting of The Nativity gained him a Slade Composition Prize. At this time some of his work was exhibited as Post-Impressionist and was considered to show the influence of early Italian artists such as Giotto.

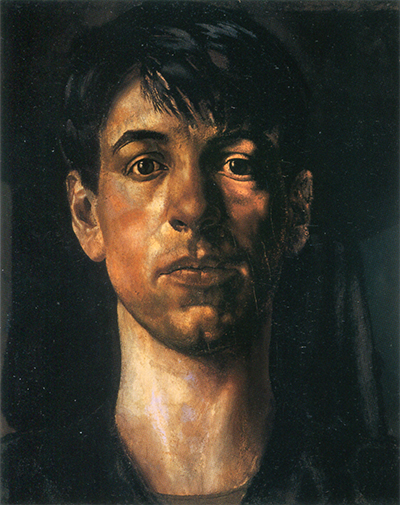

However, the themes and approaches owe as much to English writers and painters with their focus on the local, the personal and an ability to portray both darkness and innocence simultaneously. He also painted a self-portrait that was remarkable in its confident use of shade and colour. It was described as "masterly" by the art collector Edward Marsh, who bought it.

Artistic Education

His studies at the Slade were finished by the time the first World War broke out, and Spencer wanted to enlist. His mother, who had not even wanted him to go to school, was opposed to this and persuaded him to join the Royal Army Medical Corps. Spencer was eventually sent to Macedonia, where he served both in a Field Ambulance unit and in the 7th Battalion, the Berkshire Regiment.

Watching, and painting, the death and destruction around him, he would later reveal that 'I had buried so many people and saw so many dead bodies that I felt that death could not be the end of everything'. From this experience, he would return again and again to themes of death, sex, redemption and resurrection. Having observed the dead and dying around him, he began to see sex as the answer, the response to death, literally and inspirationally.

Personal Life

In sex was to be found redemption, the conquering of death and the hope of resurrection. Themes of redemption and resurrection would find some of their greatest expression in his work for the Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, with its magnificent "Resurrection of the Soldiers" on the altar wall. The dead grow from the ground like plants, pushing aside the wire and fallen crosses to reach out to one another.

There is a sense of awe, yet also once again the everyday is present in the images of floor cleaning, making beds, "Filling Tea Urns" and "Sorting and Moving Kit Bags". The paintings of camp life reflect a strong desire for order and the domestic, obsessions for the majority of soldiers who simply wanted to return to "Blighty", hearth and home. Home did not always prove to be the domestic idyll for which they yearned.

The theme of redemptive sex is also present, if ironically, in the series of controversial nude portraits of Spencer and his second wife Patricia Preece, which the artist produced in the 1930s. By this time he had married and divorced artist and fellow Slade student Hilda Carlin, and was the father of two daughters. He had been engaged to Hilda for several years, always postponing the actual marriage day until 1925, and within four years had begun his lasting obsession with Preece.

His second marriage, in 1937, was never consummated. Preece was the long-term lover of artist Dorothy Hepworth, and she maintained this relationship throughout her marriage to Spencer. The relationship was literally laid bare in "Double Nude Portrait: The Artist and his Second Wife" also known as the "Leg of mutton nude". The sensuous form of Preece sprawls across the centre of the image, legs apart, while Spencer, naked but wearing glasses, sits behind her rather awkwardly, more voyeur than husband.

Work Inspirations

In the foreground of the painting are raw joints of meat; a leg of lamb and a lamb chop, "the uncooked supper", in Spencer's description. In this phrase he once more joins the sense of the religious ("The Last Supper") with sexual yearning and redemption, along with a bleak and self-deprecating sense of humour that is sometimes overlooked in critiques of his work. The meat-like yet somehow illuminated quality of the living human flesh has been seen as prefiguring the work of Lucian Freud.

Lack of fulfilment, consummation or completion apply to both of his marriages. Despite his divorce, his relationship with Hilda never really ended. He would return to her often, still craving the domesticity that was impossible in their relationship. His daughters would recall him as a good and loving father, far from the eccentric figure that the press portrayed him in later life. As well as his marriages, he is known to have had at least two other relationships.

One of these was with Daphne Charlton, wife of the artist George Charlton, with whom he went to stay after the inevitable disintegration of his relationship with Preece. The second was with Charlotte Murray, when he was working on his magnificent shipyard images in Port Glasgow from 1939 - 1945. The relationship with his wife and family during his relationship was represented in his 1927 portrait "Hilda, Unity and Dolls", in which Hilda's body language clearly expresses her feelings, while Spencer's daughter Unity gazes out of the image, creating the connection that cannot be cut between husband and wife. The doll, the archetypal gendered toy, is a reminder of the repetitive pattern of marriage, the established (and expected) role of the female in procreation.

During the complex period of his first marriage, divorce and remarriage, Spencer was becoming well-established as a painter. His painting "The Resurrection, Cookham", exhibited in a one-man exhibition In February 1927, astonished and delighted the critics. The Times described it as "the most important picture painted by any English artist in the present century". In contrast to both marriages, this was an image of sublime harmony between the mundane and spiritual worlds. In 1932 he became an Associate of the Royal Academy and also exhibited at the prestigious Venice Biennale.

His work on the Sandham Memorial Chapel from 1927 to 1932 had partly fulfilled a concept he had developed during WWI. This was for a chapel of love that married the domestic and the religious, in which even lavatories and fireplaces played a transcendent role. These was to be the Church-House, with a chapel devoted to Carline and also, later, his lovers. The Church-House would fully develop his concept of Cookham as Heaven, with paintings expressing the transformational power of erotic love. It was a project that was never completed.

After the rapturous reception of "The Resurrection, Cookham", Spencer's 1935 exhibition works "Saint Francis and the Birds" and "The Dustman" ("The Lovers") were rejected by the Royal Academy. In "The Dustman", the dustman's beatified face as his wife lifts him into the air reflects both sexual and religious ecstasy, while his awestruck relatives and friends offer him a cabbage leaf, a teapot and a jam jar from the bin.

Critical Reception

St Francis of Assisi came in for particular criticism, being viewed as little more than a caricature. In fact, the character of the saint was based on Spencer's own father and it is difficult today to see how this painting could have been described as so offensive. Spencer resigned from the Royal Academy. Rejected by both Carline and Preece, who appropriated his house and left him with neither home nor income, he continued to work on the series known as "Christ in the Wilderness" while living in Gloucestershire close to George and Daphne Charlton. During this period, he read Thoreau's Walden.

Spencer's own redemption came in the form of a commission from the War Artists' Advisory Committee, or WAAC, organised through his agent Dudley Tooth and the Secretary of the WAAC, E.M.O'R. Dickey. This resulted in the extraordinary series of paintings of workers at Lithgows Shipyard on the River Clyde. Between 1939 and 1945, Spencer produced the “Shipbuilding on the Clyde” series, with the first purchased paintings "Burners" and "Welders" displayed in a WAAC sponsored National Gallery exhibition in May 1941.

Throughout this period Spencer was periodically returning to Epsom where Hilda and the children were living. His agent ensured that he received regular payment for his commission in Glasgow, despite Spencer's notorious refusal to sign any agreements. The series is now an important Imperial War Museum exhibit.

The Port Glasgow work is in many ways reminiscent of Spencer's war paintings. Here too, the theme of resurrection would be transformative. When passing a cemetery one evening, Spencer had a sudden revelation that this was the hill of resurrection. This encouraged a revival of his religious themed work, strongly influenced by the visions of Donne, Blake and Bunyan.

Throughout his marriages, Spencer had painted and drawn explicit images in his notebooks. In 1950, this resulted in a cause célèbre when Sir Alfred Munnings, then president of the Royal Academy, obtained some of the images and prosecuted Spencer for obscenity. Spencer had already stipulated that the "Leg of mutton nude" would never be exhibited in his lifetime. Nonetheless, Spencer was reconciled with the new President of the Royal Academy after the retirement of Munnings.

Love for Cookham

Spencer's most enduring relationship was with the village of Cookham. After the death of his first wife Hilda in 1950, he continued with his redemptive narrative paintings set in local surroundings, including "Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta". In many of his works, particularly the original war paintings and those with an overtly religious theme, Spencer takes an odd, oblique perspective, as if hovering slightly above the participants, looking into the scene.

It is an interesting and appropriate view for an artist who strove to see and share the divine in every aspect, including in the animals who share the earth with humans. His comment, 'I am on the side of angels and of dirt' shows a self-awareness that he expressed through his artistic vision. Stanley Spencer received his knighthood in 1958. Shortly afterwards, he was diagnosed with cancer. He died on December 14th 1959 and his ashes were buried in Cookham Churchyard.