William Blake was a prodigious artist and writer who changed the face of art with him innovation and social narrative. He knew little or no fame and fortune in his lifetime and did, in fact, make his living as an engraver.

Introduction

The vast majority of his work is left to us as prints from some form of engraving, be it intaglio engraving which he learned as an apprentice, or relief etching, his own invention producing vivid illuminated manuscripts. Due to the fact that printing often facilitates multiple printings, there are commonly several "original" versions of Blake's works. Today, we benefit from this happy occurrence as it provides for his work to be spread all over the world so more people can be inspired by his creative genius.

Early Training

As previously mentioned, Blake was a time-served engraver to trade. He began his apprenticeship with James Basire in August 1772 at the age of 15. His father paid £52.10 for a seven-year training. In the 18th century, engraving was a well-respected and lucrative profession so it would seem that William's father had ensured his son's wellbeing by buying this education for him. Although engraving was a very skilled and technical job, it also required great artistic ability because the copper plates which were etched with designs were traced from sketches.

In William's case, these were largely sketches of statues and crypts found in the gothic churches of London, as Basire's work predominately involved copying antiquities. Basire's training, notwithstanding, there are scholars who speculate that one of the reasons Blake found little acclaim was because he initially learned an old-fashioned style of engraving, known as line-engraving, during his apprenticeship. However, as much of Blake's most original work was created using relief etching, his own innovation, it is perhaps for another reason that he was overlooked in his lifetime.

Engraving in Blake's Time

Engraving is a process which involved carving an image onto a hard surface, in the 18th century, copper, to enable print making. This was a tremendously common trade in Blake's time. Mostly every illustration in a magazine or book, if it wasn’t hand drawn, it was printed using an engraving. However, as previously mentioned, Blake was trained in line-engraving and by the late century, stipple or mezzotint engraving were becoming much more popular and widely used.

Due to the fact that both of these more modern techniques constructed the engraving using dots instead of straight lines, they could achieve more subtle shading in the printing, and it allowed for a degree of artistic nuance. While these techniques may have been useful to Blake, his own preference to work into his images with ink and watercolour meant that the extra time required to create the plates would have slowed his process. Nonetheless, the artist's engraving skills, on a commercial basis, limited his work opportunities.

Most Famous Engravings

Perhaps one of Blake's most recognisable images is his, Isaac Newton (1795). This engraving shows the famed physicist, naked, bent over his compasses, studying his charts. The engraving was an original working to be included in his, There is No Natural Religion and it was accompanied by the inscription, "He who sees the Infinite in all things sees God. He who sees the Ratio only, sees himself only". Blake held Newton in little regard for the fact that he symbolised everything that was limiting about the world of science in his mind. He abhorred the limitations and rules involved in scientific reasoning and believed that it killed artistic expression stone dead. The rigid angles forming the images of Newton represent the restrictions and inflexibility of scientific endeavour and, in sharp contrast, the rich texture and colours of nature surrounding him symbolise creative expression. This engraving can be found in The Tate Modern in London.

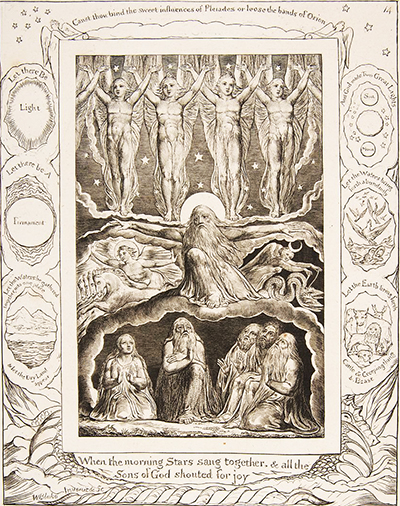

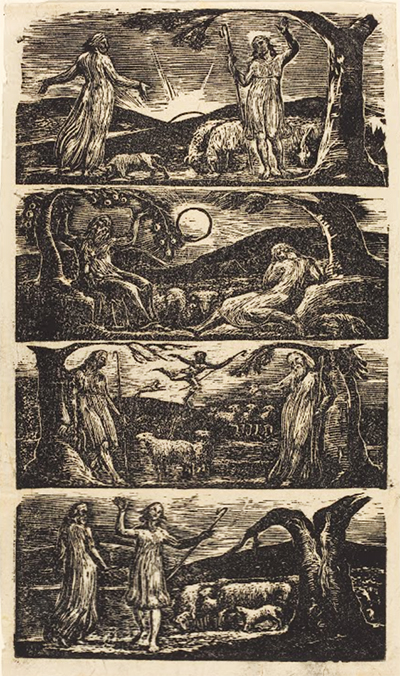

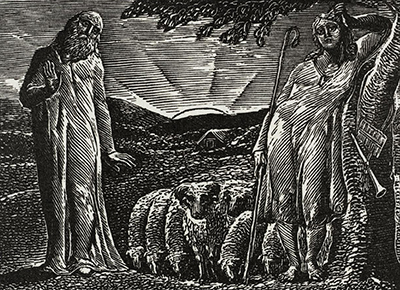

The Book of Job (1826) is widely considered to be a collection of Blake's greatest engravings. This collection of twenty-two images were commissioned by Blake's good friend, John Linell. This would be the artist's final completed book of images and they are exceptional in their design in their creation. The collection contains some of William's most enduring images, namely; Satan Smiting Job with Boils which is a graphic a terrible as it sounds, and, When the Morning Stars Sang Together a vibrant and evocative plate. As many as 315 copies of the book were printed and many of them, today, are in private collections. However, there are a number of the plates on exhibit at the Tate Gallery in London.

It is important to mention, as it is considered Blake's most influential work. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793). Set down as a parody of Biblical prophecy, and the prose is heavily informed by the political climate of the day. A time during which France and America were fighting for their independence and many men and women were suffering from poverty and disenfranchisement. The prose and the images that accompany them have taunted theologians for centuries, but widest impact it has had is on the world of literature and art, from Aldous Huxley to David Cronenberg, legions have claimed inspiration from this work.

Finally, one of Blake's most iconic and recognisable works, The Ancient of Days (1794). This watercolour etching was originally created as the cover page for Blake's prophetic book, Europe, a Prophecy. The image is that of the God Urizen, a mythological creation of Blake's imaginings, and he is crouched down to measure existence with a set of compasses. Interestingly, Urizen is in a similar attitude to William's Isaac Newton which was first printed only a year later. As in the image of Newton, Urizen is also illustrating Blake's distain for science albeit in a more existential manner. This image was said to be one of the artist's favourites additionally it was one of the few of Blake's artworks that critics actually liked. One wonders if they would have appreciated it as much if they had understood the symbolism. Due to the fact that William was so fond of this engraving, he consequently printed many copies. There are thirteen known copies in existence, most in private collection, but five at on display in museums around the world; Glasgow University Library, The British Museum, The Library of Congress, Houghton Library and The Fitzwilliam Museum. Ironically, this image was chosen by Stephen Hawking to grace the cover of his book, God Created the Integers. One imagines Blake would have found the funny side.

Blake's Legacy

It seems difficult to over-state the impact of Blake's body of work has had on the art world and society in general. He was at once an innovator and inventor, a pure artist and philosopher. Due to Blake's enormous impact on our modern culture, he continually ranks among the most important geniuses who ever live. In poll after poll, he keeps company with the likes of Einstein, Shakespeare and Da Vinci. It is little wonder then that his influence appears insidiously from literature and music to movies and graphic novel and everything in between. He is undoubtably a national treasure and society will certainly continue to appreciate his genius for generations to come.